A clumsy patching up of a broken system: Khan and Reed cut London's affordable housing targets

PLUS: leaked audio reveals a Clarion manager encouraging colleagues to produce fake evidence of displaying fire safety notices

If you have the means to do so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, which is billed monthly at just £3.50 or annually at £35. A paid subscriber has full access to the back catalogue of more than 100 posts, can comment on articles and can submit questions for Q&A pieces. All of my work is completely human-made - there is no use of AI in research, writing or editing.

If you pay £40 or more for an annual subscription, I will send you a signed copy of my first book, Show Me The Bodies. Or you can buy a copy here. My second book, Homesick can be purchased here. Even if you can’t support financially, liking this article really helps boost it up the Substack alogrithm, and forwarding the email to friends and colleagues who might be interested is really valuable. Thank you for reading!

And so there we have it. As signalled for some time, the government and London mayor Sadiq Khan have opted to cut the level of affordable housing at which developers get ‘fast-tracked’ through the planning process from 35% to 20%, as well as providing a series of tax cuts, grant schemes and reductions in regulatory demands to encourage builders to “ramp up” development.

They argue that this is pragmatism, a necessary response to a genuinely serious crisis in London’s build numbers. I will say at the outset that I do understand the problem. The position in London is genuinely very serious, and it’s easy to see why the government felt the need to act.

Indeed, there are serious voices I respect - not just the usual band of industry lobbyists and their outriders - who think that these measures are a good step, and a sensibly measured response to a situation which offered few easy answers.

In the end, though, I disagree. I cannot see how cutting affordable housing targets is a step forward towards solving the housing crisis, and the response appears to misunderstand both the scale and cause of the current problems. While badged as short term pragmatism, what it really reveals is an ongoing absence of long-term thinking and a clumsy patching up of a system that remains broken.

Explaining this requires a proper understanding of the current crisis, and more clarity on what London actually needs from new development.

A proper understanding of the crisis

House building in London has plummeted this year. In the first three months of the year, builders started just 3,248 new homes, and the city is on track for 5,000 starts in the calendar year. Since 2000, London has tended to see around 30,000 homes built every year - which means we’re running at about a sixth of normal levels.

This will kick through into economic consequences: labourers will be out of work, contractors will go bust, the manufacturers of building materials will slow down and the whole ecosystem of professionals that feed off the construction and sale of new homes will struggle.

The government’s hope is that by offering a time-limited boost to developers (the new affordable housing thresholds and tax cuts are set to expire in 2028), it will persuade builders to boost their output in this otherwise fallow period. The argument, therefore, is that 20% of something beats 35% of nothing.

The trouble is first that this misunderstands the cause and scale of the crisis. Lots of things have gone wrong at the same time for private developers in London, but the primary reason why they are building fewer homes is economic, not political.

In June, just 26 newly built homes sold across the whole of the city. Yes - you read that right - twenty six. 2. 6. That is a tiny, tiny number in such a big city, and explains why builders are reluctant to put spades in the ground. Put blunty, people aren’t buying them and building homes people won’t buy is a bad move for a developer.

Several things have happened to lead to this point. First, demand for ‘off-plan’ sales (ie, selling an option on the home before it is built, usually to an investor) have been collapsing for years. This is partly due to Brexit, partly due to changes in the global economy. London house builders used to sell up to 60% of schemes in this way, which provided an early slug of finance to pay for the development. Now they’re lucky to get 10%. So this means many more of the flats built have to go to actual individuals, who buy them once they are built to either live in or rent out.

But these sales have dried up to a trickle. Landlord investors are less keen than they were, given tax rises and changing rental laws. Individual buyers can’t afford flats anymore because of the rise in interest rates and the end of Help to Buy. There is also a good argument that years of revelations about crap build conditions and the dreadful experiences of leaseholders mean more people finally recognise that buying a newly built apartment from a volume developer is a potential ticket to years of stress and expense, not the glossy dream portrayed in the sales brochure.

What should really happen at this point is that prices should fall. Flats should be sold at a rate that consumers are willing to pay. If that means builders don’t make the profits they expected, or even book losses, then tough. This is capitalism. You took a risk on an investment and it went bad. Your profits were never supposed to be guaranteed.

Except, that isn’t what’s happening. Instead builders are holding off on construction, hoping that profits can return. Around London, hundreds of development sites are gated and padlocked. Some of these are not being built out because they are waiting for regulatory approval, and some are struggling because the contractor has gone bust. But in others, the developer has simply stopped, because the profits are no longer there. According to the consultancy Molior: “Work is deliberately on hold because the sales market is so weak.”

What they are terrified of is prices falling. “As sales rates are low, prices are clearly too high,” the consultancy says. Even on the sites which are moving, builders are releasing flats onto the market very slowly, to ensure prices remain high. In completed schemes builders are renting out properties built for sale, hoping to sell them later when profit margins are higher.

In fairness to the industry what makes this particularly difficult is the other side of the coin: at the same time as sales reducing, build costs have exploded. Building materials and labour costs have boomed - rising at well above inflation. This means, according once more to Molior, that in the areas of London where properties sell at under £650 per square foot (more than half the city, basically all of the cheaper bits outside the centre and south west), development is unviable: build costs are so high that you simply can’t make a profit from building and selling a new home.

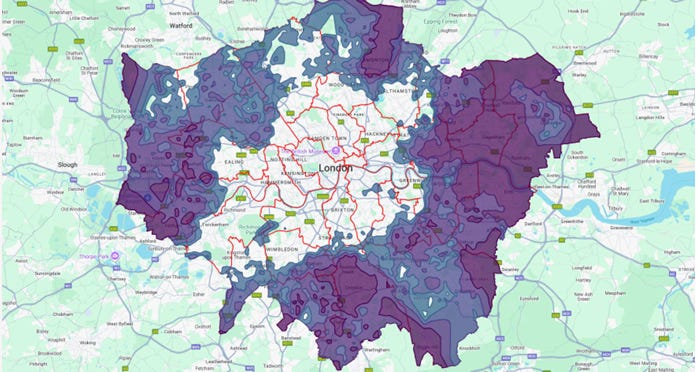

Areas of London where build costs are unviable: it costs more to build than you can make from selling (image: Molior)

Here’s the kicker though. On this analysis, which has been extremely influential in persuading the government and the mayor to put this rescue package together, this lack of viability would remain true “even if the land is provided free and there are no planning obligations like CIL and affordable housing”. So, how will cutting CIL and affordable housing help? If profits remain below costs in most of the city, the builders still aren’t going to build. In fact, the affordable housing element (sold in bulk to an affordable housing provider), is probably the easiest part to shift in most of these schemes (although not necessarily easy - many affordable housing providers have stopped buying homes from private builders, citing years of poor quality, and complex management agreements which make looking after the homes an administrative nightmare).

Of course - there are other factors. The delays caused by the Building Safety Regulator’s gateway process are a massive deal in a London market where 96% of new build properties are in blocks of flats, and land prices mean more new build projects than elsewhere in the country go above 18m. New requirements for things like sustainable urban drainage and the prevention of overheating are obviously crucial in the context of the climate crisis, but they do add cost.

But the BSR delays are fixable as the system beds in and the cost of new regulatory requirements could be absorbed in a more bouyant market. The crisis of house building in London is primarily an economic conundrum - prices are too high, but the industry is unwilling to let them fall.

What happens next depends on the economy. The rise in build costs has several causes - a bit of Brexit, a bit of inflation, a bit of the fall out from war in Ukraine and rising energy prices, and a bit of domestic turbulence as the market has scaled up and down post-pandemic. This turloil could even out in coming years and cause build prices to fall from their current peaks.

Equally, builders seem to be holding out and crossing their fingers, hoping for interest rates to come down (or some other intervention like Help to Buy to kick in) to allow them to sell their units at the rates they originally planned to.

If either of these things happen, then the market will recover, and this package will simply gift builders higher margins at the taxpayer’s expense.

But if neither of these things happen, then the market will remain stalled in the areas where it is currently unviable. What will change is that in the areas where private development is viable, the builders get to make bigger profits from the schemes they bring forward. A small grey area where profits are available, but the schemes are close to the line is the only area where it will make a genuine difference. And if we’d waited a few years, the viability picture might have changed and these sites would have been built out with higher rates of affordable housing.

Remember, that although individual developments have become less viable, builders have still managed to keep their profits high. Berkeley, which operates almost exclusively in London, booked profits of more than £500m last year. That’s less than the close-to-£1bn figure it made at the peak of the 2010s market, but it still represents a very flush bank balance for an industry going cap-in-hand to government and asking for help.

More clarity on what London actually needs from new development

A big problem at the core of Labour’s housing policy is that in setting a 1.5m homes target, they decided to pursue an output rather than an outcome. That means when they face crises like this they enter them without clear ideas of what they want to achieve.

Why do we want 1.5m homes? Is it to drive up economic growth projections to ease the current fiscal crisis? Is it to reduce house prices for young professionals on the cusp of buying? Or is it - as the most idealistic claim - to reduce housing pressure for everyone and ultimately homelessness?

The current intervention into the London market reveals the problem of this confusion. One of the structural problems in the UK’s housing market is that house prices are prevented from falling when economic logic says they should. Right now, London’s new build house prices are too high, and should fall. The government’s bail out is seeking to avoid that outcome, by allowing builders to shore up their profits elsewhere, so they can keep waiting on the schemes which are currently underwater.

As it is, the change to affordable housing quotas will have perverse consequences. Land owners will now sell developable land at higher rates, on the expectation that developers will only need to fund 10% affordable housing (the remainder being covered by government). But this will bake that cost into the system - you won’t be able to reverse it very easily if the market recovers. And schemes progressing with more than 20% affordable housing are likely to withdraw and resubmit planning permission to take account of the lower rates. This will slow down these sites, and mean they deliver lower rates of affordable homes.

Then you have the decision to use government cash directly to support private house builders - first through funding half of their affordable housing contribution with grant, and second through a package of City Hall money to remove barriers to construction.

All government expenditure is money that could have been used on something else - to acquire homes on the open market to relieve homelessness, for example, or to help fully affordable non-profit schemes stand up. Instead, we are ordering housing charities to buy ‘affordable’ homes from private builders, in order to shore up their balance sheets. It is a poor political choice.

Better solutions would have come from asking what London needs from new development. The city currently faces a series of acute, linked crises. Homelessness is at record, unsustainable levels, with one in 20 children in the city homeless. This is wrecking futures and crippling local authority budgets, with temporary accommodation costs for councils hitting around £6.5m every day.

The city is also facing an exodus of key workers and lower income families, on whom its economy is utterly dependent. Future challenges of an aging population and climate change are far too close to be ignored, and the city’s housing is poorly adapted to cope.

These are problems which the private house building model is extremely poorly adapted to solve. Backers of private developers argue that all housing supply helps - because it reduces overall pressure. Providing homes at the top of the market reduces competition in the middle, which then reduces competition at the bottom, they say.

But as I wrote a couple of weeks ago, this trickle-down logic works much better on paper than in reality - it doesn’t operate within a particular local boundary and works over decades (if at all). It is not an immediate solution to a critical crisis.

Instead, what private builders are currently doing is competing for an ever decreasing pool of buyers. Even the Build to Rent model - which more directly interacts with the rental market - is flawed in this way. New Build to Rent developments are priced so highly that even with the extraordinary rental market in the capital, they fill up very slowly. They are currently leasing at 26 homes per month - which means a new 450 home development will take almost a year and a half to fully let. Before then, the apartments will stand empty.

Viewed like this, if the current economic crisis breaks the current speculative development model, that could be viewed as a good thing. If it breaks their dominance over developable land in London, other models get a fighting chance.

All of which leads me to a question which some of my less temperate readers might have already screamed at their screen.

This is all well and good Peter, but what the hell should we be doing instead?

Good question, if impolitely posed. I would argue that the current crisis actually offered the chance for some good short-term solutions, and some opportunities for longer-term change - if we had been bold enough.

In the short-term, the collapse of the sales market for new builds actually offered the government an incredible opportunity to carry out some distressed asset purchases ie, they could have bought up schemes which are non-viable to the developer at a discount, or funded local councils to do so.

This would have seen the developer take a haircut on their expected profits but then, well, they are sophisticated private businesses who made bets on the property market which went bad. They shouldn’t expect the state to rescue them.

The homes acquired like this could have been offered to key worker and homeless households, which would have immediately reduced the cost to London boroughs of temporary accommodation. The government grant being pushed into supporting developers could have been used to do this instead.

The government also has a fairly generous £39bn affordable homes programme planned - although most of that spending is due to come in from 2029 onwards. Pushing some of that money in now would have given the supply chains in the capital a boost, while also getting affordable housing out of the ground faster.

And as for the schemes under construction, some degree of price rebalancing must happen - even if it costs the builders money. We cannot keep artificially inflating prices, because that comes with a huge social cost, even if it avoids short-term economic pain. Builders need to learn that if the market turns they will have to sell at a loss, not sit tight and hope for government to sort it out for them.

Longer term, a strategy should ask how we diversify the mix of players in London’s housing market. Other cities around the world make great use of co-operative housing and community land trusts. There are also longer term, patient investors who will invest in the development of a place in pursuit of long-term growth in value, rather than just turning out flats for the next financial statement to the city. We could also start zoning areas for affordable and social house building, which prevents land prices accelerating based on speculative profits. These models cannot flourish while volume builders own the key sites. If the crisis caused them to sell, then that was an opportunity.

We should also be looking to ease London’s housing pressures outside of London - converting some agricultural land around the city to residential, especially near stations, but crucially doing so with cast-iron affordable and social housing commitments.

An industrial strategy should also look at why build and labour costs have got so high - especially given that many building products are made in the UK. Sorting out our domestic supply chain and labour market is a must.

The truth is that the volume and speculative building model has grossly failed London. Construction reached a recent high in the last years of the 2010s, with more than 45,000 homes built in a single year. But this did very little to ease the captial’s real world housing pressures.

Instead, builders cashed in on off-plan sales, and rentals to wealthy international students. The needs of the ordinary Londoner were forgotten.

These steps would require bravery, clarity of long-term thought and a willingness to accept a drop off in numbers as a step towards a better future model. The current package - on my reading at least - looks a lot more like a short-term panic and an attempt to entrench a broken status quo.

‘If you don’t get access tomorrow, just put it up on a plain bit of wall, take a picture, it’s done’

Very worrying audio leaked to Sky News this week revealed a manager at the giant housing association Clarion pressing a colleague to fake evidence that they had displayed a safety notice in the communal areas of a block of flats.

You can read the story and listen to the audio here. The story deserves a little bit of unpacking.

The audio was recorded in 2022. At the time, Clarion was offering residents in its blocks ‘person-centred fire risk assessments’ (PCFRAs), is they were disabled and they felt they might be at increased risk of a fire.

The manager’s team was responsible for putting notices up asking residents to contact the organisation to get such an assessment completed. For some unknown reason, their team was struggling to get access to the relevant communal areas, and so came the encouragement to pretend. In the call, the manager made several references to “hitting targets”.

So. What to make of it?

First, it is important to place it in context. Shocking as it is, there are some mitigating factors. Clarion was actually pushing beyond the requirements of the law in offering PCFRAs at this point in time (it had adopted fire chief’s guidance for supported housing for its general needs housing).

The landlord says it has carried out an investigation since - checking fire documentation and signage in all properties managed by the individual concerned, as well as interviewing team members. The investigation concluded that it was an isolated issue caused by a single member of staff. The staff member was dismissed in 2024.

All of this said, there are still very good reasons to worry. PCFRAs were not a legal requirement in 2022, but will become one as part of the residential PEEPs regulations next April. These regulations rely entirely on residents coming forward to social landlords and asking for support, and set a low-legal bar of “reasonable endeavours” for landlords to make residents aware of the opportunity.

This story therefore is a gigantic red flag, warning that this might not be done properly - and requires clarity about how it should be carried out, oversight and enforcement. Even in a non-Grenfell scale fire, people with disabilities are at major risk in high rise buildings.

It also provides a salutary warning regarding fire safety management and the use of targets. Too often, a target becomes the aim in itself, and this leads to bad behaviour - like juking fire risk assessments to downgrade the priority of recommended actions.

It also continues to raise the long-standing point about professional standards in social housing. Unlike a nurse or a social worker, there is no professional standards board to investigate this (unnamed) manager and discipline her, strike her off or force her to attend training. There is every chance she has moved on from Clarion to another social landlord, where she will once more be responsible for life safety issues affecting tenants. This is not good, and illustrates why this is something Grenfell survivors and bereaved have pushed so hard to change.

A Clarion Housing Group spokesperson said: “This matter related to a poster about Person-Centred Fire Risk Assessments in one neighbourhood within a single region of our portfolio. These posters are not a legal requirement or formal fire safety notice, but form part of our broader commitment to resident safety and good practice in how we communicate important information.”

“In 2023, our HR team received an email from a former employee raising concerns, but no supporting evidence was provided despite our request. When an audio recording was shared with us in September 2024, we immediately launched a full investigation and took appropriate action.

“It is deeply regrettable that information was not shared sooner, as this would have enabled earlier action. Fire safety remains our top priority across all Clarion homes.”

My new book Homesick is out now, and available here:

‘Apps set the gold standard with his Grenfell coverage. With Homesick, he dismantles the sham of UK housing policy – razor-sharp, stylish, and morally unflinching.’ ―Darren McGarvey, author of Poverty Safari

‘A beautifully thorough, mesmerising and big-hearted book that manages to bring housing policy alive without losing any of the detail or analysis.’ ―Isabel Hardman, author of Why We Get the Wrong Politicians

This was my second post of the week - partly because I will be away on half-term duty next week. The Substack will return in the first week of November. Catch up on the back catalogue here.

If you have the means to do so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, which is billed monthly at just £3.50 or annually at £35. A paid subscriber has full access to the back catalogue of more than 100 posts, can comment on articles and can submit questions for Q&A pieces. All of my work is completely human-made - there is no use of AI in research, writing or editing. Students, campaigners, tenants, people on low incomes - hit reply and ask, and I’ll gift a free subscription.

If you pay £40 or more for an annual subscription, I will send you a signed copy of my first book, Show Me The Bodies. Or you can buy a copy here. My second book, Homesick can be purchased here. Even if you can’t support financially, liking this article really helps boost it up the Substack alogrithm, and forwarding the email to friends and colleagues who might be interested is really valuable. Thank you for reading!

Your distressed purchase option is exactly what happened in the early 1990's with the Government's Housing Market Package and the Housing Corporation's deferred HAG (Housing Association Grant) schemes.

This all makes sense. I suspect another factor in the declining demand for flats is the stalling of leasehold reform. Spiralling service charges have made many flats impossible to sell and made buyers rightly wary of this problematic tenure. The Leasehold & Commonhold Reform Act was passed in May 2024 but most of it still awaits secondary legislation. In November Pennycook announced his ambition to bring in Commonhold this term, but we’ve yet to see a sunset clause requiring all new build flats to be commonhold. As a result ‘hitting targets’ in flat building would simply create yet more problematic leasehold tenures. The clauses on service charge reform must be passed before I’d advise anyone to buy leasehold.

Finally I wish we could stop using the term ‘housebuilding’ as a generic term that includes high-rise leasehold with all its specific problems, as well as low-rise freeholds.